Thanks Chris for your on-line history of Kynochs which gives us material which might have been omitted from the official company histories.Yes, Richard, as Stokkie says, the business has been transformed over the last few decades with all the original activities such as ammunition and, a bit or a lot later, non-ferrous semi manufacture (sheet, rod, wire etc.), titanium and other new metals, zip fasteners, Amal carburettors and many, many more now gone, sometimes to new owners or completely disappeared. It has been that regular re-invention which has facilitated the Company's survival in its second century of existence whereas its other major Birmingham industrial counterparts, Lucas, BSA, Dunlop, GEC, Austin and others are now just names in the memory. Even Kynoch's one time owner from the mid-1920s, ICI, has long since gone (but its successor continues to meet the pension obligations, thank goodness!) There remains some IMI manufacturing in the UK (possibly a bit on part of the old, main site - I'm not sure whether that's still the case) but changing markets, technology, products have led to the vast majority of it occurring in overseas IMI factories in several parts of the world. And the disappearance of the old, vast Witton manufacturing site where much of it used to happen. Total transformation, unrecognisable to those with longer memories - and still here!

Stokkie has pointed you to the online potted history, a bit of my own work of many years ago (and in need of the more recent years being added, when I get around to it) and that shows how things evolved in the critical 1980s, 90s and early 2000s. And the whole remarkable history from 1862 shows a constant evolution of the business and a fight for survival, although nothing as drastic as the changes over those decades.

Chris

-

Welcome to this forum . We are a worldwide group with a common interest in Birmingham and its history. While here, please follow a few simple rules. We ask that you respect other members, thank those who have helped you and please keep your contributions on-topic with the thread.

We do hope you enjoy your visit. BHF Admin Team

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Kynochs

- Thread starter Ponz

- Start date

ChrisM

Gone but not forgotten R.I.P

I think that an answer to that complicated question would take up a full academic thesis or fairly dense book, Richard! (Which, in any case, I rather doubt whether I would be capable of producing ....)Thank you Chris! What I don’t understand is why the city fathers didn’t fight (&win) to save some of those businesses or replacements. All industrialized countries have gone through this and reinvented themselves with something more than a social action. NJ where I lived when I came to the US along with the New England states continue to reinvent themselves after their original industries changed or went away.

I’m not pointing the finger of blame but change is difficult but usually rewarding.........

I'll just try and summarise what, for me at least, seemed to me to have been some of the major reasons behind the decline in Birmingham's manufacturing base. Just jotted down today off the top of my head, not slept on and probably incomplete - and possibly disagreed with:

- an immediately postwar industrial complacency - we won, didn't we? - because the whole industrial emphasis was on producing products and getting them to the docks in order to improve the balance of payments disaster facing the country. The world needed them, however good or outdated they were; and the country certainly depended on the revenue, having exhausted itself, financially and in other ways, ensuring its own survival and the freeing of the rest of Europe, all of course with the significant help of the USA.

(In December 1945 my father led a reparations team on behalf of the British non-ferrous metals industry and toured a ruined North Germany, chalking up items of kit which were later shipped back to the UK and installed in various UK factories by the side of other outdated, pre-war equipment. The Germans replaced these with brand new, up-to-date machinery, paid for by U.S aid. We preferred to use the latter for other purposes).

- industrial management which was set in its ways, was in some cases lacking in competence and the professionalism necessary in this new world; and was generally not equipped/had difficulty in adjusting to the pace of change elsewhere. There was a reluctance to invest (or practical difficulty in investing) in equipment and product development, as Germany and Japan - and later, others - were doing to a greater degree.

- general social attitudes which led to excessive power and influence landing up in the hands of trade unions, some with a particular political agenda, and the resulting regular, damaging disruption in factories . (Any of us involved in manufacturing industry who lived through the 1970s will recall what a simply appalling time that was).

- increasing competition from abroad, often with more efficient facilities, better labour relations, better productivity and, above all, far lower labour costs.

- increasing lack of understanding of/sympathy for manufacturing industry within a metropolitan-based government - government in the broadest sense, including the Civil Service - leading to an absence of plan and guidance. All reinforced by a general perception that the country's future wealth and well-being did not depend on manufacturing (that vaguely unpleasant activity mainly undertaken somewhere up north, thank goodness) but on the provision of services.

I don't think we'll explore the matter of intervention - or non-intervention - by the city fathers at this present time of local Council problems!.

(When I was still working, I coined the phrase "It's the mugs what makes things". In other words, I looked back on my original choice of career and thought that, with hindsight, it probably hadn't been the best thing to have done: the sensible decision would have been to select something in the wider world, much more ordered and lacking in daily crisis, such as accountancy, law, banking, advertising, marketing, IT, insurance or the Civil Service - anything other than wrestling with the sort of problems which faced anybody in a big UK company trying to manufacture something. These problems I witnessed at first hand and saw them taxing every ounce of the intelligence, knowledge, resilience, energy, personal qualities and, yes, intellect (contrary to popular belief!) of extremely capable people. Perhaps they still do, in the few big companies which survive).

My own family experience was no doubt typical.

IMI fed and clothed my brother, my sister and me. It continued to do so with the three pairs of boys we produced between us. Not a single one of those six went near manufacturing as a career choice. All went into services, of one sort or another.

In the mid-1950s I scraped my way into a leading university. I went up with three other Sutton/Streetly/Four Oaks/ Erdington lads. Three of us had fathers in manufacturing: IMI, Dunlop and another Birmingham company; I've forgotten the fourth. Of that same three of us, the choice was IMI, Gillette (London) and a Lancashire glass manufacturer. But I suspect that, in the case of their children, manufacturing featured nowhere in their later careers, as it didn't with mine.

Life had moved on and British society with it, for better or for worse.

I regret, too, that so much of major, surviving UK manufacturing activity belongs to others. But I console myself that much of the expertise remains in this country, as does a goodly portion of the wealth which the activity generates. And that British manufacturing, presumably in Birmingham as elsewhere, tends now to be concentrated in smaller companies who have often carved out specialist niches in their markets where they can use the many skills still available to them and prosper with their help.

All just my opinion, and probably not worth debating much further, except in as far as it refers directly to Birmingham and its specific history....

Chris

Hi

I think the munitions side was reduced after the big explosion in I think it was shot gun cartriges. I was actually in Witton when it went up though not terribly loud it was obviously a very powerful explosion. I can't remember what it was and what caused though the Birmingham Mail had an article on it.

Brian

I think the munitions side was reduced after the big explosion in I think it was shot gun cartriges. I was actually in Witton when it went up though not terribly loud it was obviously a very powerful explosion. I can't remember what it was and what caused though the Birmingham Mail had an article on it.

Brian

Pedrocut

Master Barmmie

Kynoch munitions at its peak 1880-1918….1918 employed around 20,000….war production and Government contracts.

1919 slump. Arklow plant closed.

1920s rationalisation and folded into ICI in 1926. Munitions now one branch of giant chemical empire.

By 1930s production at a small fraction of pre WW1 peak.

Rearmament revived production. And day/ night working at Witton. Temporary. Empire dissolved and exports orders collapsed.

Nationalisation of defence contracts. Cheap imports.

1970s now IMI, concentrated in industrial and specialist ammo.

1979 explosion (3 killed) renewed safety concerns and bad publicity.

1980s Thatcher privatisation. Into Royal Ordinance, later BAE systems.

1990 Kynoch brand, mainly sporting cartridges contracted out and not Manufacturered in Birmingham.

1919 slump. Arklow plant closed.

1920s rationalisation and folded into ICI in 1926. Munitions now one branch of giant chemical empire.

By 1930s production at a small fraction of pre WW1 peak.

Rearmament revived production. And day/ night working at Witton. Temporary. Empire dissolved and exports orders collapsed.

Nationalisation of defence contracts. Cheap imports.

1970s now IMI, concentrated in industrial and specialist ammo.

1979 explosion (3 killed) renewed safety concerns and bad publicity.

1980s Thatcher privatisation. Into Royal Ordinance, later BAE systems.

1990 Kynoch brand, mainly sporting cartridges contracted out and not Manufacturered in Birmingham.

Richard Dye

master brummie

Thank you Chris for that, I will take a deep breath and say my piece: At the on set we are in violent agreement with what you have said. An observation about British industrial leadership in the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s, 90’s 2000 is that it was poor at best and not willing or could not change. It was more about who you were and not what you could do. Not everyone and everywhere. A company in your own back yard, Cincinnati Milling Machine Company, the world changed, so did they. Now Milacron a completely different company, a few miles away Dunlop, failed to pivot, they were the best of the best and there were many more like them. Some like the GEC got caught up in an acquisition frenzy, having worked for three private equities they could have done better. Lucas another one.I think that an answer to that complicated question would take up a full academic thesis or fairly dense book, Richard! (Which, in any case, I rather doubt whether I would be capable of producing ....)

I'll just try and summarise what, for me at least, seemed to me to have been some of the major reasons behind the decline in Birmingham's manufacturing base. Just jotted down today off the top of my head, not slept on and probably incomplete - and possibly disagreed with:

- an immediately postwar industrial complacency - we won, didn't we? - because the whole industrial emphasis was on producing products and getting them to the docks in order to improve the balance of payments disaster facing the country. The world needed them, however good or outdated they were; and the country certainly depended on the revenue, having exhausted itself, financially and in other ways, ensuring its own survival and the freeing of the rest of Europe, all of course with the significant help of the USA.

(In December 1945 my father led a reparations team on behalf of the British non-ferrous metals industry and toured a ruined North Germany, chalking up items of kit which were later shipped back to the UK and installed in various UK factories by the side of other outdated, pre-war equipment. The Germans replaced these with brand new, up-to-date machinery, paid for by U.S aid. We preferred to use the latter for other purposes).

- industrial management which was set in its ways, was in some cases lacking in competence and the professionalism necessary in this new world; and was generally not equipped/had difficulty in adjusting to the pace of change elsewhere. There was a reluctance to invest (or practical difficulty in investing) in equipment and product development, as Germany and Japan - and later, others - were doing to a greater degree.

- general social attitudes which led to excessive power and influence landing up in the hands of trade unions, some with a particular political agenda, and the resulting regular, damaging disruption in factories . (Any of us involved in manufacturing industry who lived through the 1970s will recall what a simply appalling time that was).

- increasing competition from abroad, often with more efficient facilities, better labour relations, better productivity and, above all, far lower labour costs.

- increasing lack of understanding of/sympathy for manufacturing industry within a metropolitan-based government - government in the broadest sense, including the Civil Service - leading to an absence of plan and guidance. All reinforced by a general perception that the country's future wealth and well-being did not depend on manufacturing (that vaguely unpleasant activity mainly undertaken somewhere up north, thank goodness) but on the provision of services.

I don't think we'll explore the matter of intervention - or non-intervention - by the city fathers at this present time of local Council problems!.

(When I was still working, I coined the phrase "It's the mugs what makes things". In other words, I looked back on my original choice of career and thought that, with hindsight, it probably hadn't been the best thing to have done: the sensible decision would have been to select something in the wider world, much more ordered and lacking in daily crisis, such as accountancy, law, banking, advertising, marketing, IT, insurance or the Civil Service - anything other than wrestling with the sort of problems which faced anybody in a big UK company trying to manufacture something. These problems I witnessed at first hand and saw them taxing every ounce of the intelligence, knowledge, resilience, energy, personal qualities and, yes, intellect (contrary to popular belief!) of extremely capable people. Perhaps they still do, in the few big companies which survive).

My own family experience was no doubt typical.

IMI fed and clothed my brother, my sister and me. It continued to do so with the three pairs of boys we produced between us. Not a single one of those six went near manufacturing as a career choice. All went into services, of one sort or another.

In the mid-1950s I scraped my way into a leading university. I went up with three other Sutton/Streetly/Four Oaks/ Erdington lads. Three of us had fathers in manufacturing: IMI, Dunlop and another Birmingham company; I've forgotten the fourth. Of that same three of us, the choice was IMI, Gillette (London) and a Lancashire glass manufacturer. But I suspect that, in the case of their children, manufacturing featured nowhere in their later careers, as it didn't with mine.

Life had moved on and British society with it, for better or for worse.

I regret, too, that so much of major, surviving UK manufacturing activity belongs to others. But I console myself that much of the expertise remains in this country, as does a goodly portion of the wealth which the activity generates. And that British manufacturing, presumably in Birmingham as elsewhere, tends now to be concentrated in smaller companies who have often carved out specialist niches in their markets where they can use the many skills still available to them and prosper with their help.

All just my opinion, and probably not worth debating much further, except in as far as it refers directly to Birmingham and its specific history....

Chris

Newly married I was hired by an old time American company in the automotive supply sector who had hired an EVP who was an astrophysicist/ engineer who I turn hired an electrical engineer from Raytheon who in-turn hired me working at General Foods. Different backgrounds different industries. Our mission was to improve productivity and Quality, and we did. For me it was a career ride of a lifetime! We changed a lot of things based on science and performance. In 20 years we went from 50 ppm to 240ppm with less labor took market share and hired more people, and yes we were unionized. I have worked with unions, it’s difficult but you can, you need to be credible and respectful.

The quality of many British products was poor and continued that way particularly in the automotive sector, and getting the government involved was the worse thing that could have been done, the results are evident. Lee Iacocca a true car person and turned Chrysler around for many years with new and reliable products until Daimler came along and now Stellantis which is another loosing politically run organization which is currently in an almost death spiral.

Companies like Apple, Oracle HP etc all started in a garage and now are global giants all in our lifetime. 60 through 2000 is plenty of time to change and we are 25 years on from that.

Change and failure to change rings a death bell, you might not like it but it’s true. A current metric in manufacturing is robots per 10,000 people. The UK has half the robots of other EU countries and a third less than Japan, Germany, France and a little more than one tenth that of South Korea who is the world leader.

Hindsight is 20/20, history is a great teacher, let us ALL learn from it!

Richard Dye

master brummie

Where are they as a producer? Economy could be a consumer which means the profits go elsewhere. For example: US/China Japan &, yes the UK could be the 5th largest, metrics would be helpful. Not sure but is the EU considered one Economy?Some say that the UK is the 5th largest economy in the world.

mw0njm.

A Brummie Dude

i AgreeGetting way off topic !

superdad3

master brummie

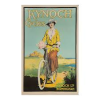

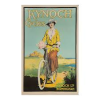

Like many folk, I have always connected Kynochs with the munitions industry. One of my interests is looking at old Birmingham ephemera on Ebay and I was quite surprised to come across this poster:

Originally issued as a promotional poster in the 1920s it was an instant success and has regularly been reprinted.

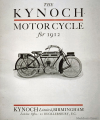

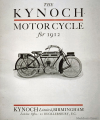

Initially only components were made from the late 1890s at the new bicycle plant at the Lion Works, Witton with complete bicycles from about 1923. Small and brief part of Kynochs production. They also made motor cycles from 1904-1913.

Lion Works 1890s.

Originally issued as a promotional poster in the 1920s it was an instant success and has regularly been reprinted.

Initially only components were made from the late 1890s at the new bicycle plant at the Lion Works, Witton with complete bicycles from about 1923. Small and brief part of Kynochs production. They also made motor cycles from 1904-1913.

Lion Works 1890s.