-

Welcome to this forum . We are a worldwide group with a common interest in Birmingham and its history. While here, please follow a few simple rules. We ask that you respect other members, thank those who have helped you and please keep your contributions on-topic with the thread.

We do hope you enjoy your visit. BHF Admin Team

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

F. Smith 31 New Street Birmingham (1850s ?)

- Thread starter Matchboxhouse

- Start date

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

Thank you. Please can you tell me the source for your dating?1840/41

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

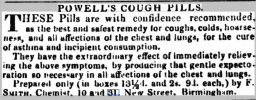

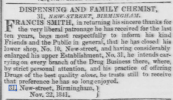

Thank you very much indeed.F Smith advertising at 31 New Street in those years (Chemist)

Birmingham Journal.

F Smith , chemists & druggists are listed in directories in 1839 and 1841 at no 10 and 31 New St. By 1845 they are Smith & Churchill, chemists and agents for Royal Navy, Army, East India, fire and Insurance. Perhaps the very fancy box is for one of these illustrious clients

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

Thank you for your details. I did not expect this level of information. So lovely to be able to add to my records these details about this "match / candle" steel container. The name F.Smith is not normally associated with matches. My "matchbox" collection started in 1966, and I like to research the items in my collection.

There was a "Birmingham Match Company". However, the details of this victorian company remain a mystery to reserchers of matchboxes. They made "congreve" matches according to what is stated on the pieces that remain on one matchbox label.

There was a "Birmingham Match Company". However, the details of this victorian company remain a mystery to reserchers of matchboxes. They made "congreve" matches according to what is stated on the pieces that remain on one matchbox label.

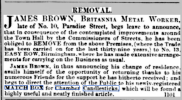

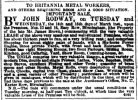

There was a firm of match manufacturers in Birmingham whose owner was David Bermingham. They were apparently on the corner of Aston Road North and Phillips St, giving the Aston Road North address in their earlier mentions and the Phillips st one later,

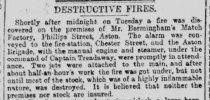

The firm seems to have started in the mid 1860s, there were a number of fires and they appear several times in the newpapers, but had one in

1888 and soon after were listed as tin box makers, under william Bermingham

The firm seems to have started in the mid 1860s, there were a number of fires and they appear several times in the newpapers, but had one in

1888 and soon after were listed as tin box makers, under william Bermingham

pjmburns

master brummie

The notices in posts 9 and 10 name him as Francis.In trade directories from the 1830s–1850s, an F. (Frederick) Smith is indeed listed at 31 New Street, described variously as a “chemist,” “druggist,” “optician,” and “philosophical instrument maker.”

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

Thank you. I am aware of details about David Bermingham. However, no matchbox labels seem to have been preserved. More of a mystery are details about the Birmingham Match Co. Only the attached label known.There was a firm of match manufacturers in Birmingham whose owner was David Bermingham. They were apparently on the corner of Aston Road North and Phillips St, giving the Aston Road North address in their earlier mentions and the Phillips st one later,

View attachment 211705

The firm seems to have started in the mid 1860s, there were a number of fires and they appear several times in the newpapers, but had one in

1888 and soon after were listed as tin box makers, under william Bermingham

View attachment 211707View attachment 211709View attachment 211711View attachment 211713View attachment 211715

Attachments

Pedrocut

Master Barmmie

“The “Congreve Match” was named (somewhat misleadingly) after Sir William Congreve, who was better known for his military rockets.

Around 1828–1830, several British chemists (notably John Walker and Samuel Jones) sold “Congreve’s lights” — small sticks tipped with chemicals that ignited by friction on sandpaper or chemically treated paper. Birmingham, already strong in chemical trades, japanning, and small metal goods, soon became a manufacturing centre for match tins, strikers, and matches.”

Around 1828–1830, several British chemists (notably John Walker and Samuel Jones) sold “Congreve’s lights” — small sticks tipped with chemicals that ignited by friction on sandpaper or chemically treated paper. Birmingham, already strong in chemical trades, japanning, and small metal goods, soon became a manufacturing centre for match tins, strikers, and matches.”

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

I would like to put the record straight here, as much misleading information circulates on the internet. John Walker invented "friction lights" in 1826, and the first record of a sale by him was on the 7th April 1827. He stopped making them when Samual Jones and Watt's copied his formular, naming them "Lucifers". Congreve matches came later.“The “Congreve Match” was named (somewhat misleadingly) after Sir William Congreve, who was better known for his military rockets.

Around 1828–1830, several British chemists (notably John Walker and Samuel Jones) sold “Congreve’s lights” — small sticks tipped with chemicals that ignited by friction on sandpaper or chemically treated paper. Birmingham, already strong in chemical trades, japanning, and small metal goods, soon became a manufacturing centre for match tins, strikers, and matches.”

Pedrocut

Master Barmmie

To be fair to Walker the internet it does inform…

Walker’s sales book shows limited sales through 1827–1829; he didn’t turn it into a business, but sources don’t prove he quit because Jones copied him—only that he didn’t patent or scale up, so others (Jones, Holden’s circle, etc.) took the market. (Wikipedia)

“Congreve match” is best understood as a name used for early friction matches, not a brand-new, later invention. Victorian writers and modern glossaries use “Congreve” for the chlorate/antimony/sulfur friction type and say the name honoured Sir William Congreve (the rocketry man). In practice the term overlapped with “lucifer” in the late 1820s–1830s rather than arriving long after. (Wiktionary)

Walker’s sales book shows limited sales through 1827–1829; he didn’t turn it into a business, but sources don’t prove he quit because Jones copied him—only that he didn’t patent or scale up, so others (Jones, Holden’s circle, etc.) took the market. (Wikipedia)

“Congreve match” is best understood as a name used for early friction matches, not a brand-new, later invention. Victorian writers and modern glossaries use “Congreve” for the chlorate/antimony/sulfur friction type and say the name honoured Sir William Congreve (the rocketry man). In practice the term overlapped with “lucifer” in the late 1820s–1830s rather than arriving long after. (Wiktionary)

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

The Congreve match (from around 1831) also included phosphorus, and was an improvement on the Lucifer. (Walker's Friction Lights / Lucifer's are non-phosphoric friction matches). I agree that the use of "Lucifer" was so established in England that the use of the name Congreve was little used here. It was far more commonly used in Austria and Germany. We see many matchboxes there that have Congreve printed on the matchbox labels. "Congreve's succeeded Lucifer's" [ref: 'A Dictionary of Applied Chemistry' (published in 1922)].To be fair to Walker the internet it does inform…

Walker’s sales book shows limited sales through 1827–1829; he didn’t turn it into a business, but sources don’t prove he quit because Jones copied him—only that he didn’t patent or scale up, so others (Jones, Holden’s circle, etc.) took the market. (Wikipedia)

“Congreve match” is best understood as a name used for early friction matches, not a brand-new, later invention. Victorian writers and modern glossaries use “Congreve” for the chlorate/antimony/sulfur friction type and say the name honoured Sir William Congreve (the rocketry man). In practice the term overlapped with “lucifer” in the late 1820s–1830s rather than arriving long after. (Wiktionary)

Pedrocut

Master Barmmie

Going back to the first post.

It is possible that F Smith, the chemist, would buy the locally finished boxes, a durable container with a striker and a small vial compartment. Birmingham (and the Black Country) was a national centre for japanned tinplate and small pressed metalwares. Dozens of firms could cheaply make hinged pocket boxes and die-struck brass nameplates to order. The red-and-black japanned finish and brass nameplate are consistent with Birmingham japanning and tinplate work, an industry centred in the city at that time.

A New Street chemist’s nameplate would signal quality and accountability. Customers may return to Smith for refills/chemicals, so branding the box made commercial sense even if the metalwork came from a nearby works.

It is possible that F Smith, the chemist, would buy the locally finished boxes, a durable container with a striker and a small vial compartment. Birmingham (and the Black Country) was a national centre for japanned tinplate and small pressed metalwares. Dozens of firms could cheaply make hinged pocket boxes and die-struck brass nameplates to order. The red-and-black japanned finish and brass nameplate are consistent with Birmingham japanning and tinplate work, an industry centred in the city at that time.

A New Street chemist’s nameplate would signal quality and accountability. Customers may return to Smith for refills/chemicals, so branding the box made commercial sense even if the metalwork came from a nearby works.

Matchboxhouse

proper brummie kid

Thank you for all your posts. I had hoped that F.Smith was either a maker of matches or metal boxes for them. I now know that essentally they were Chemists that also traded in other products. They were surrounded by metal working workshops that could support them. This is certainly an interesting "match" piece and now treasured in my collection as an early container for matches.Going back to the first post.

It is possible that F Smith, the chemist, would buy the locally finished boxes, a durable container with a striker and a small vial compartment. Birmingham (and the Black Country) was a national centre for japanned tinplate and small pressed metalwares. Dozens of firms could cheaply make hinged pocket boxes and die-struck brass nameplates to order. The red-and-black japanned finish and brass nameplate are consistent with Birmingham japanning and tinplate work, an industry centred in the city at that time.

A New Street chemist’s nameplate would signal quality and accountability. Customers may return to Smith for refills/chemicals, so branding the box made commercial sense even if the metalwork came from a nearby works.

Pedrocut

Master Barmmie

Could well be !

“A “Match Box for Chamber Candlesticks” refers to an early combined candleholder and match keeper, sometimes with a friction striker or enclosed section for “instantaneous lights.” These were a popular domestic innovation in the 1830s–1850s, bridging chemists’ chemical matches and metalware manufacture.”

“A “Match Box for Chamber Candlesticks” refers to an early combined candleholder and match keeper, sometimes with a friction striker or enclosed section for “instantaneous lights.” These were a popular domestic innovation in the 1830s–1850s, bridging chemists’ chemical matches and metalware manufacture.”