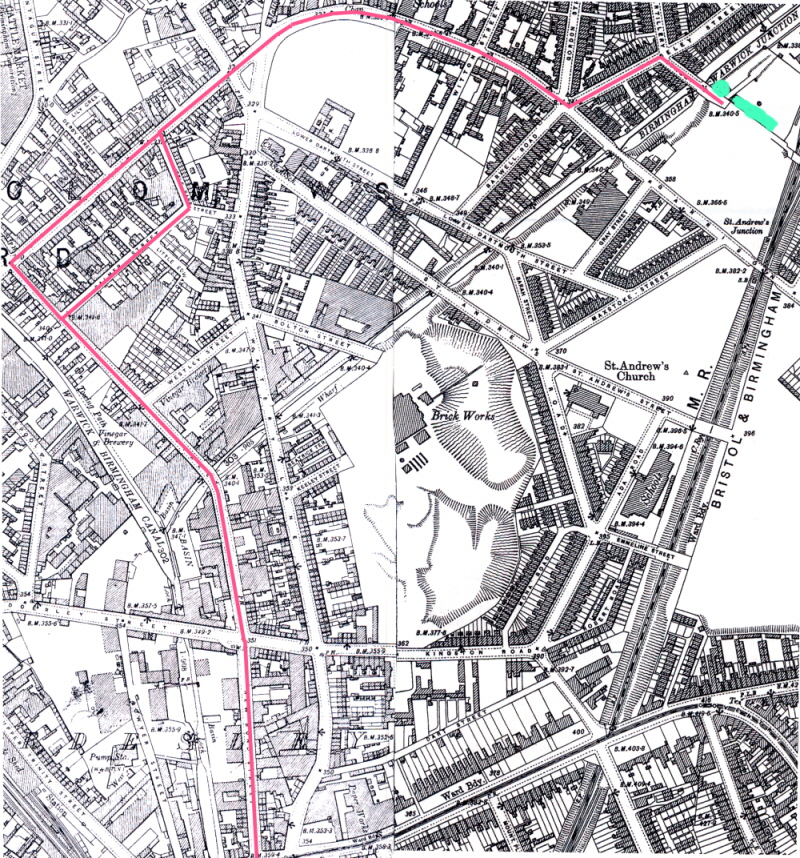

This is not a company I had come across before. The 1890 OS map shows a Compressed air works in the triangle between the canal, railway and Artillery St.

If the survey had taken place in 1883 then this would not have been shown, and if the survey had occurred in 1893 then the building would have been there but not marked compressed air works.

1. Start of Project.

The aim of the company was to provide a supply of compressed air to an area of Birmingham in the wards of Deritend, St Martins, St Bartholomew &

Bordesley, covering an area of about 1.5 sq miles from a central station. Compressed air as a power source was not new. Murdoch had used it at the Soho works for one of the machines many years before, a similar system was reported to be used in connection to the Mersey Tunnel in Liverpool , while in Paris apparently it was used extensively to generate electricity, having 30 miles of mains, and also as a power source for several thousand clocks!

The air would be distributed by a series of mains comprising cast iron pipes totalling a length if about 23 miles carrying air at a pressure of about 40 lb/sq inch (psi). The main mains would be 24 inch cast iron pipes, with side mains of 7 inches. In order to carry out the works necessary a parliamentary bill was required, and in the bill’s presentation it was claimed that the saving to the factories would on average be about 20-30% over their normal fuel costs. . A report compiled by the organisers is available online at https://archive.org/details/reportonascheme00robigoog . It seems to have been assumed that the compressed air would be used to power dynamos to produce electricity for the machines or as a direct power source. The scheme was aimed only at workshops, but the chairman of the committee investigating the Bill commented that he was surprised the scheme was not being extended to use for powering tramways.

.

The prospectus for the Company was issued in 1886 and, as so often happens, was somewhat extravagant in its claims, postulating the development of things such as air clocks and air cooling apparatus. The area to be covered was somewhat smaller than initially suggested, excluding Bordesley and being circumscribed by the Midland Railway, Belgrave St and Belgrave Road to Bristol St, Bromsgrove St, Jamaica Row, Moor St, Belmont row, Lawley St & Garrison St. The initial plan was to provide 15,000 horse power, from 6 triple expansion compound condenser beam engines, produced by Fowler of Leeds, to work compressors. The engines would be powered by boilers heated by gas produced from 12 Wilsons patent gas producers in which steam is passed through heated coal. Initially four steam engines were envisaged. At a meeting of the British Association in that year the Chairman, Sir James Douglas commented that “Birmingham has provided itself with perfect sewage, water and gas schemes, and is now going to launch into a scheme for securing a perfect distribution of motive power, which it required more than any other town on the face of the earth.”

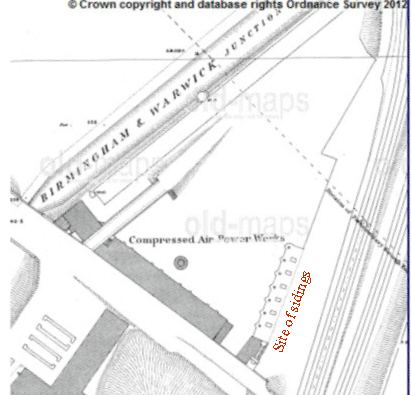

Work commenced on building the central works in March 1887. By 24th February 1888 all the foundations were completed, the four engine houses built alongside Artillery road, and one of the engines almost completely installed. The seven gas producers had been installed, together with the coal platform & chute. I would guess that the view shown on the c 1889 map below (Fig.1) shows the progress at about that point. Here the sidings have not yet been installed (though I have marked where they will be), but the gas producers that are beside the sidings are there, as is the coal chute at the end of the gas producers next to Artillery road. The idea was that coal would be delivered in wagons by rail and poured down the chute directly into the gas producers. At this time seven out of the nineteen boilers had been installed in the basement of the engine houses, and three more were nearly complete. The progress of the plans had been delayed somewhat as permission to commence the laying of the mains in the streets was only given by the council on 24th Dec 1887. However work is said to have commenced in laying the pipes the next day. Can’t see workman starting work on Christmas Day in the 21st century. By the time of this report one length of 500yds of 24inch pipe had been laid and fully tested at 90 psi., though the working pressure would only be 50 psi. It was noted that there was a figure of £13,000 due in calls of arrears (where shares have been purchased, but money not paid for them on time).

Fig.1.map c 1889 Birmingham Compressed Air Power Co works

If the survey had taken place in 1883 then this would not have been shown, and if the survey had occurred in 1893 then the building would have been there but not marked compressed air works.

1. Start of Project.

The aim of the company was to provide a supply of compressed air to an area of Birmingham in the wards of Deritend, St Martins, St Bartholomew &

Bordesley, covering an area of about 1.5 sq miles from a central station. Compressed air as a power source was not new. Murdoch had used it at the Soho works for one of the machines many years before, a similar system was reported to be used in connection to the Mersey Tunnel in Liverpool , while in Paris apparently it was used extensively to generate electricity, having 30 miles of mains, and also as a power source for several thousand clocks!

The air would be distributed by a series of mains comprising cast iron pipes totalling a length if about 23 miles carrying air at a pressure of about 40 lb/sq inch (psi). The main mains would be 24 inch cast iron pipes, with side mains of 7 inches. In order to carry out the works necessary a parliamentary bill was required, and in the bill’s presentation it was claimed that the saving to the factories would on average be about 20-30% over their normal fuel costs. . A report compiled by the organisers is available online at https://archive.org/details/reportonascheme00robigoog . It seems to have been assumed that the compressed air would be used to power dynamos to produce electricity for the machines or as a direct power source. The scheme was aimed only at workshops, but the chairman of the committee investigating the Bill commented that he was surprised the scheme was not being extended to use for powering tramways.

.

The prospectus for the Company was issued in 1886 and, as so often happens, was somewhat extravagant in its claims, postulating the development of things such as air clocks and air cooling apparatus. The area to be covered was somewhat smaller than initially suggested, excluding Bordesley and being circumscribed by the Midland Railway, Belgrave St and Belgrave Road to Bristol St, Bromsgrove St, Jamaica Row, Moor St, Belmont row, Lawley St & Garrison St. The initial plan was to provide 15,000 horse power, from 6 triple expansion compound condenser beam engines, produced by Fowler of Leeds, to work compressors. The engines would be powered by boilers heated by gas produced from 12 Wilsons patent gas producers in which steam is passed through heated coal. Initially four steam engines were envisaged. At a meeting of the British Association in that year the Chairman, Sir James Douglas commented that “Birmingham has provided itself with perfect sewage, water and gas schemes, and is now going to launch into a scheme for securing a perfect distribution of motive power, which it required more than any other town on the face of the earth.”

Work commenced on building the central works in March 1887. By 24th February 1888 all the foundations were completed, the four engine houses built alongside Artillery road, and one of the engines almost completely installed. The seven gas producers had been installed, together with the coal platform & chute. I would guess that the view shown on the c 1889 map below (Fig.1) shows the progress at about that point. Here the sidings have not yet been installed (though I have marked where they will be), but the gas producers that are beside the sidings are there, as is the coal chute at the end of the gas producers next to Artillery road. The idea was that coal would be delivered in wagons by rail and poured down the chute directly into the gas producers. At this time seven out of the nineteen boilers had been installed in the basement of the engine houses, and three more were nearly complete. The progress of the plans had been delayed somewhat as permission to commence the laying of the mains in the streets was only given by the council on 24th Dec 1887. However work is said to have commenced in laying the pipes the next day. Can’t see workman starting work on Christmas Day in the 21st century. By the time of this report one length of 500yds of 24inch pipe had been laid and fully tested at 90 psi., though the working pressure would only be 50 psi. It was noted that there was a figure of £13,000 due in calls of arrears (where shares have been purchased, but money not paid for them on time).

Fig.1.map c 1889 Birmingham Compressed Air Power Co works

Last edited: